The Art of Controlling Cultural Meaning: Art Nouveau and Art Deco in the Third Reich

In November 2025, Sotheby’s sold the most expensive modern artwork ever at auction—for $236.4 million. The painting is not only a Viennese Secession-Art Nouveau masterpiece that prompted collectors to bid generously, but it also has a fascinating history behind it—what it stood for and how it was part of a campaign to control cultural meaning.

When modernist style was labeled degenerate art

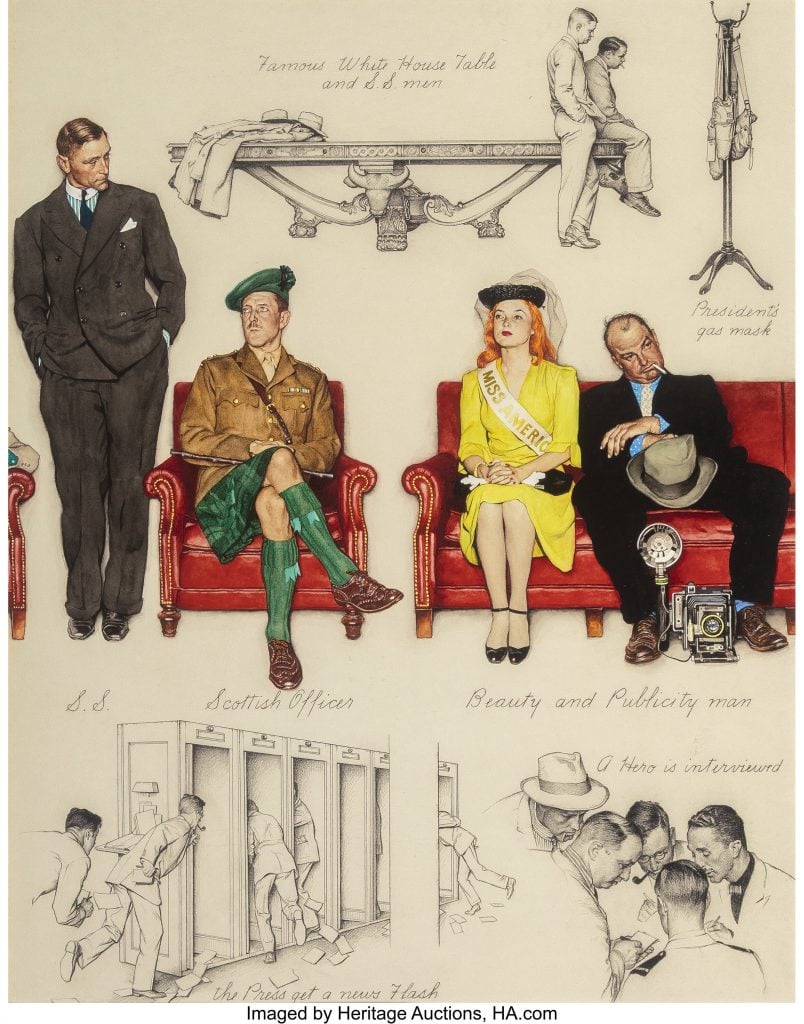

Gustav Klimt’s painting of 20-year-old Elisabeth Lederer, daughter of Vienna’s Jewish cultural elite and patron, was completed in 1916, just two years before the death of the artist. After the 1938 annexation of Austria, it was seized by the Nazis. Remarkably, it escaped destruction, and then found its way back to the family, and entered Leonard Lauder’s collection in the 1980s. What makes the story fascinating is that Elisabeth herself, then in her forties, was saved from prosecution because of the portrait. Klimt had become an internationally acclaimed artist by that time, Elisabeth’s arrest would have brought attention to Nazi persecutions. According to contemporary accounts, Elisabeth even claimed that Klimt, who was not Jewish, was her father.

The Nazi regime of the Third Reich systematically confiscated art that did not conform to its ideology. Styles deemed “un-German”, including modernism, such as expressed in the Art Nouveau movement (or Jugendstil, as it was known in Germany), were frequently targeted. They were denounced as “degenerate art” because of their modernist style and cosmopolitan nuance—blending influences from Asia and other parts of the globe—and moreover, because of the artists’ tie with wealthy Jewish patrons.

Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer by Gustav Klimt. (wikimedia.org)

Art Nouveau emerged as a revolt against historicism

Art Nouveau (roughly 1890–1910) is commonly described as a form of decorative modernism, notable for its long, sinuous lines, organic motifs, and Japonisme and other Asian influences. This is demonstrated in the portrait of Elisabeth, where a Japanese-inspired patterning decorates the background. Art Nouveau, often associated with Brussels, emerged as a revolt against the historicism of 19th century art.

With a craft‑centered ethos that sought to unify fine and applied arts, Art Nouveau—influenced by the earlier Arts and Crafts movement in Britain—regarded factory production as producing low-quality goods that degraded both objects and workers. Art Nouveau’s emphasis on artisanal skill was a response to industrial modernity. While the movement did not reject technology, it objected to the lack of artistry in mass production and sought to elevate decorative handwork and craft as a means of social and aesthetic reform.

Art Nouveau was a movement with a social and political agenda

Art Nouveau was avant-garde, the style of the new generation and emergent bourgeoisie eager to distinguish themselves from the old nobility and conservative society. While largely an urban and often elitist movement, it sought to improve everyday life—promoting well-being, a renewed connection to nature, and greater beauty and functionality in the domestic environment—not just for the wealthy but also the working class.

Interestingly, Art Nouveau developed its distinct regional traits across Europe. For example, dominant colors signal local identity: Vienna used black and white; Brussels identified with orange and green; Spain favored bright, saturated colors; and Italy chose soft pastels and earthy tones. In some regions, the style carried a political statement, such as in Finland, Art Nouveau motifs became associated with cultural and political emancipation from Russia. In the Czech lands and Poland, folk motifs and historic references with modern forms were blended to assert national culture under imperial rule. Similarly, in Catalonia, Art Nouveau was an expression of the people’s struggle for independence.

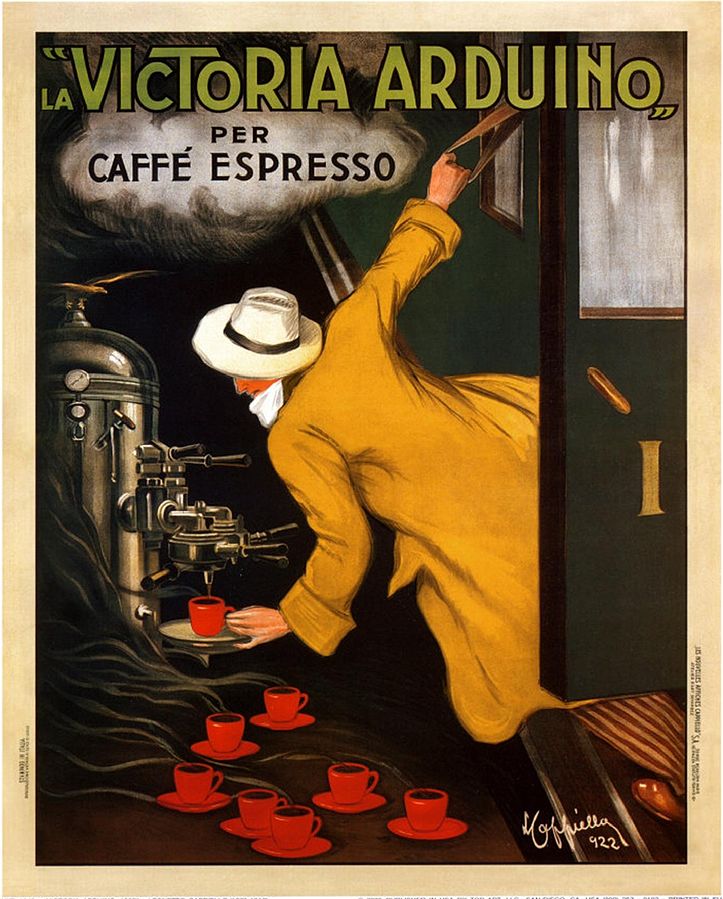

A somewhat scandalized advertisement for the Job cigarette company (1896) by Czech painter and graphic artist Alphonse Mucha who became the defining figure of Art Nouveau. (theartstory.org)

Thus, Art Nouveau functioned as a coherent movement with a social and political agenda: achieving societal progress and sovereignty.

Inevitably, Art Nouveau lost its popularity after World War I following the collapse of traditional patronage and a postwar recovery that needed mass production, consumerism, and affordable design. Despite this fact, when the Nazi regime came into power decades later, it still confiscated Art Nouveau and other modernist works for their perceived internationalism, moral inferiority, and past associations with Jewish patrons.

Art Deco became a symbol of multiculturalism, cosmopolitan and urban lifestyle

As the Art Nouveau movement waned in the 1910s, what would become Art Deco in the 1920s began to emerge. This new art movement, closely associated with Paris, echoed the shift in design philosophy that was in line with the postwar years of rebuilding. With its simple design for easy production and reproducibility, it reflected the rapid industrialization and vast technological advancements taking place. Its clean lines, bold colors, and streamlined geometric forms symbolized modernity, progress, structure, and order, but its decorative richness separated it from modernism. Patterns of zigzags, square spirals, and aerodynamic curves reflected international grandeur and glamour. Art Deco too drew inspiration from various cultures, including Africa, Asia, and the Americas, as well as from different historical periods—symbolizing postwar multiculturalism, and an urban, cosmopolitan lifestyle.

The Côte d’Azur Pullman Express poster (1929) was designed by French artist Fix‑Masseau who worked in the Art Deco idiom that dominated railway and travel posters of the late 1920s and 1930s. (peoplesgdarchive.org)

While Art Nouveau was reformist and artisanal oriented, Art Deco had revolutionized design for a modern machine‑age society.

Art Deco, like Art Nouveau, was elitist at its height

Art Deco shaped the designs of public goods, such as transportation and social housing, but like Art Nouveau, it remained elitist at its height. With its consumerist ethos, the style represented the interests of the urban middle class with spending power. In this way, Art Deco functioned as an innovative and progressive force in the development of modern industrial capitalism, where mass products with short lifespan were created to stimulate demand.

Post–World War I witnessed the rise of a consumer-oriented middle class which benefited from interwar economic expansion, gradually replacing the dominance of the old aristocratic and bourgeois elites. At the same time, the middle class distinguished itself from working‑class and socialist aesthetics, defining its identity through upwardly mobile urbanity, a lifestyle of consumerism and modernity, and the professional status of white‑collar employment. Among this emerging class was the emancipated “New Woman” of the Weimar era which ended in 1933.

Art Deco inspired designs were used to signify progress

The Nazi campaign sought to systematically control cultural meaning. From 1933 onward, all art was regulated by the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda. Any work not aligned to Nazi ideology of Aryan purity and nationalism was targeted. Both Art Nouveau and Art Deco, with their hybrid concepts and modernist styles, were condemned as corrupt by a regime that upheld the supposed superiority of Greek and Roman classical art.

Poster created by commercial illustrator and poster artist Ludwig Hohlwein for Deutsche Lufthansa in 1936, promoting the Berlin Summer Olympics and reflecting nationalistic pride. (pinterest.com)

Nevertheless, when the regime could benefit from a style, it adapted it for political purposes. This is the case with Art Deco, the prevailing design trend during Nazis’ rise to power. In posters and other propaganda media, the regime used Art Deco-inspired elements—streamlined geometry and bold palette—to signify progress, structure, order, discipline, and heroism, in order to persuade and mobilize the population, especially the youth.

The regime mastered the art of controlling cultural meaning

The Nazi regime implemented selective suppression in its cultural policies. Rather than fully banning everything that conflicted with its ideology, the regime instead systematically censored, repressed, or reshaped representations. For example, in the case of the gender ideology that the “New Woman” symbolized, the regime restricted or banned publications that promoted it. Lesbian periodicals such as Die Freundin and Frauenliebe/Garçonne were banned, while liberal magazines such as Die Dame and Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung were adapted or coopted to align with Nazi objectives. At the same time, the regime consistently propagated an alternative imagery of womanhood that emphasized motherhood and patriotism, which would eventually dismantle the “New Woman”.

Cover of the German fashion and lifestyle magazine Die Dame, depicting the style of the New Woman, published in March 1929. (wikimedia.org)

Thus, the story behind Gustav Klimt’s painting of Elisabeth Lederer demonstrates how art—just as other media in its various forms—can be used as a tool to control society, uphold ideology, and legitimize power, whether completely suppressed by being banned, or coopted, adapted, and reshaped to serve those in power. Art Nouveau was one of the modernist art forms frequently targeted for banning, while elements of Art Deco were often adapted and reshaped to conform to the Nazi regime’s cultural and political rhetoric. This illustrates one of the many ways in which a regime could master the art of controlling cultural meaning: art, far beyond aesthetics, becomes a political instrument.

-Some Thoughts from the Cappuccino Girl- (2025)

#history #art #fascism #Germany #WorldWar1

You might be interested to read: The Salute of Tyranny From Global Power to Existential Anxieties: How Colonialism and Migration Shape the UK

Top image: Euronews.com

Sources

Greenhalgh, Paul (2000) ‘Art Nouveau: Politics and Style.’ History Today Vol. 50 Issue 4 April. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/art-nouveau-politics-and-style [22 November 2025].

Horth, Elisabeth (2009) The Social Agenda of Art Nouveau. Collectors Weekly. https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/guest-column-the-social-agenda-of-art-nouveau [22 November 2025].

Mallya, Sanjana (n.d.) Art Deco and Its Global Influences. Rethinking the Future. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a11195-art-deco-and-its-global-influences [22 November 2025].

Middlemiss, Matteo (2018) Why Was Art Nouveau the Art Revolt People Were looking for? The Flame Tree Blog. https://blog.flametreepublishing.com/art-of-fine-gifts/why-was-art-nouveau-the-art-revolt-people-were-looking-for [21 November 2025].

Myrvang, Christine (2015) Art Deco: The Era That Lingers in Spirit. BI Norwegian Business School. https://www.bi.no/en/research/business-review/articles/2015/09/art-deco-the-era-that-lingers-in-spirit-/ [22 November 2025].

Pound, Cath (2018) What Art Nouveau Can Teach Us about National Identity. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180525-what-art-nouveau-can-teach-us-about-national-identity [22 November 2025].

Smith, Elizabeth Anne (2025) Beauty in the Face of Horror: Fashion, Femininity, and Identity During the Holocaust. Thesis. Washington State University. Online PDF document [29 November 2025].

Wikipedia (2025) Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berliner_Illustrirte_Zeitung [29 November 2025].

Wikipedia (2024) Die Freundin. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Die_Freundin [29 November 2025].

POPULAR TOPICS

#subculture

Gurlesque: Poetics of the Bizarre, Ugly, and Feminine

#films

Mrs. Robinson, Countercultures, and Politics

#history

The Dutch Golden Age, Golden for Whom?

I also write articles here: https://feministpassion.blogspot.com/