So You Want to See the President! Nostalgia, Neoliberalism, and Political Polarization

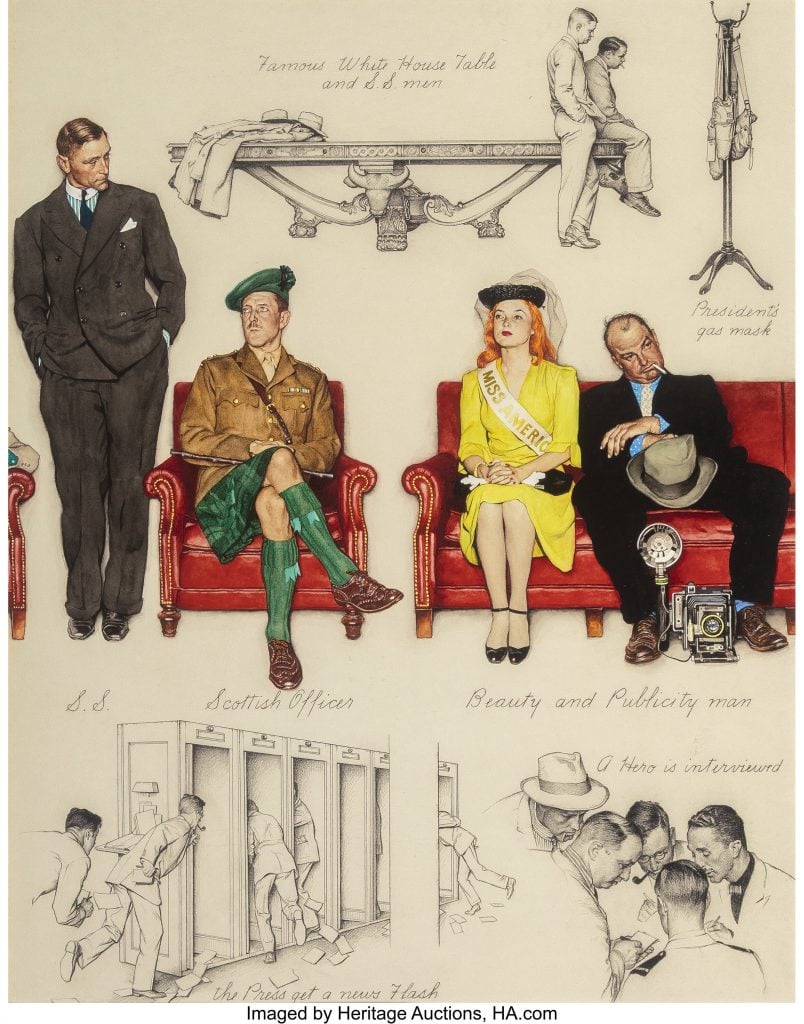

So You Want to See the President!, that's the title of the four-panel suite of paintings that, for decades, hung in the White House. Painted in 1943 by celebrated American artist Norman Rockwell, the suite portrays the waiting area outside the Oval Office, where citizens from various professions and officials gathered in hopes to meet the President. The paintings captured the democratic spirit of the era. At the height of World War II, it reflected a unifying vision of American society.

Amid the anxieties of wartime and economic uncertainty, Rockwell crafted images that evoked the nostalgia of the American Golden Age, depicting the comforts of family life and a secure home. Mainstream media often promoted this image of prosperity—which Rockwell was able to translate so well onto his canvas—to soften the realities of economic hardship and racial tension. Conservative outlets like The Saturday Evening Post used the psychology of nostalgia to soothe public unease rooted in economic vulnerability and to foster a sense of cohesion amid a racialized society. Norman Rockwell would later become a cultural icon, best known for his illustrations in The Saturday Evening Post, from the interwar years to the early decades of the Cold War.

The post-First World War period was marked by economic expansion and rapid growth, followed by a flourishing cultural environment and shifting social norms, epitomized by the emergence of the flapper counterculture. It was also a time of political progress as women finally secured the right to vote. Yet the Roaring Twenties was also a decade of economic disparity—low wages for the urban working class and persistent hardship for rural Americans—leaving many vulnerable. Not surprisingly, it was a period of continued racial tensions, marked by the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the passage of the restrictive Immigration Act of 1924.

Interestingly, Rockwell’s celebrated depictions of the idealized male breadwinner nuclear family—spanning over four decades—continue to resonate with segments of the American public today.

Nevertheless, under the strict editorial direction of The Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell’s images not only masked the social tensions but also obscured the shifting norms reshaping American society. Readers were deflected from reality by scenes that told the story of a stable and harmonious American society centered on the “typical” male breadwinner and female homemaker nuclear family. Absent in these images were the independent flappers and hardly visible were the working-class, particularly women, both white and of color.

Twenty-five years later, the welfare policies and economic boom of post-World War II made the idealized male breadwinner family attainable, although very briefly, for middle-class and upper-class households. Yet this image of mainly white, suburban families, continued to be perpetuated by mainstream media for decades. It was an image that also aligned with the US government’s Cold War narrative, which promoted the nuclear family as a symbol of capitalist superiority in contrast to the collectivist ideals of communism.

Following the civil rights movement that shifted perceptions about society, new laws and policies were enacted to reduce racial and gender inequality. These reforms transformed social norms and values around family and sexuality, and shaped institutions. However, not all segments of society embraced these changes. Rockwell himself grew weary of the editorial constraints imposed by The Saturday Evening Post and, in 1963, left to work for Look magazine. There, he crafted some of his most controversial works that confronted the inequalities and tensions shaping America.

Like feminism, the far-right views women’s role in care work as undervalued by society; however, far-right supporters generally attribute this to the cultural hegemony of neoliberalism and liberal feminism.

Interestingly, Rockwell’s celebrated depictions of the idealized male breadwinner nuclear family—spanning over four decades—continue to resonate with segments of the American public today. On various digital platforms, some women from diverse ethnic backgrounds who support far-right ideologies have expressed dissatisfaction with contemporary society, describing a sense of peace and empowerment upon embracing traditional gender roles. This discontent often cites feminism for promoting a perception that privileges professional women over traditional homemakers—diminishing the cultural value of housewives and of men as primary providers and protectors.

Like feminism, the far-right views women’s role in care work as undervalued by society; however, far-right supporters generally attribute this to the cultural hegemony of neoliberalism and liberal feminism. This hegemony, in their view, has stigmatized traditional values and gender roles, where masculinity is more often loathed than encouraged and men are no longer seen as women’s protector, both in the social and economic sense. Such cultural dominance, they argue, are among the factors contributing to the decline of what they consider “true American values.”

Furthermore, the hegemony that promotes multiculturalism and diversity is perceived by far-right supporters as contributing to unresolved societal issues, such as job insecurity, limited access to public goods, and increase in crime rates, including violence against women. The increase in immigration is often cited as a cause of these problems even when such claims are not reflected in data and statistics.

The far-right movement, therefore, seeks to restore traditional “native” values as a way of deconstructing what they perceive as a broken society. However, the dissatisfaction is often attributed to shifting cultural norms, while in fact, it stems from systemic issues. The lack of accessible and trustworthy childcare, the absence of family-friendly labor policies, and the persistence of traditional gender roles that impose a double burden on women all contribute to the difficulties faced by many—particularly mothers.

Scholars interpret this as a backlash against the failure of neoliberal governance to deliver broad-based economic security and social cohesion.

Moreover, the movement asserts that saving America from perceived cultural decadence requires strengthening a monocultural national identity and reasserting national control over the economy, as economic sovereignty is framed as a moral imperative to restore traditional family values and cultural order. This vision reflects its supporters’ economic anxieties and fears of cultural displacement. Scholars interpret this as a backlash against the failure of neoliberal governance to deliver broad-based economic security and social cohesion.

Scholars have observed that neoliberal policies in the United States have deepened inequality: wages have stagnated for much of the working class, labor protections and social safety nets have eroded, and corporate profits have soared—concentrating wealth at the top. Privatization and deregulation have rendered public goods such as higher education, healthcare, and housing increasingly unaffordable. Critics of neoliberalism argue that policies prioritizing market efficiency over social equity have fueled job insecurity, housing shortages, rising rents, and racialized vulnerability. These systemic failures have contributed to cultural fragmentation, institutional distrust, and adverse political polarization.

So You Want to See the President!—which was commissioned in 1943 by Stephen T. Early, Roosevelt’s press secretary—depicted various groups in American society, conveying a unifying vision of democracy. Yet it reflects a white, middle-class lens on civic participation, mirroring the exclusionary politics and cultural norms of its time, in which structural diversity and inequality were obscured. The suite was removed from the White House in 2022 following a family ownership dispute and is scheduled for auction. While the paintings hold significant historical value, the suite’s removal is timely given that the country seriously needs to bridge political polarization. To move forward, reflection is urgently needed to envision a post-neoliberal governance that centers equity, care economies, labor protections, and democratic accountability, while dismantling structures that perpetuate marginalization and safeguard concentrated wealth.

-Some Thoughts from the Cappuccino Girl- (2025)

#history #art #WorldWar1 #WorldWar2 #US #Politics #feminism

You might be interested to read: From Global Power to Existential Anxieties: How Colonialism and Migration Shape the UK

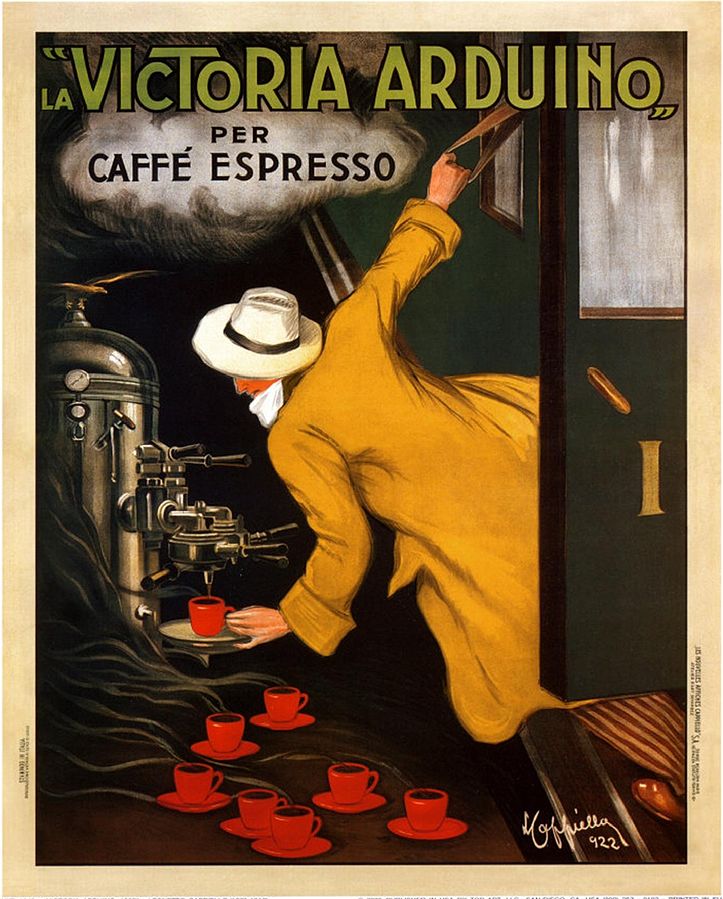

Image: Artnet News

Sources:

Ainsworth, Garrett (2024) ‘Why Neoliberalism Has Failed Us: How Republican Economic Policies Promote Inequality.’ Michigan Journal of Economics. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/mje/2024/03/18/why-neoliberalism-has-failed-us-how-republican-economic-policies-promote-inequality/ [8 November 2025].

Bradatan, Anastasia (2023) The Overlooked Roles of Women in Far-Right Extremist Organizations and How to Prevent Their Further Radicalization. Fordham Law Voting Rights and Democracy Project. https://fordhamdemocracyproject.com/2023/04/26/the-overlooked-roles-of-women-in-far-right-extremist-organizations [19 October 2025].

Campion, Kristy and Kiriloi M. Ingram (2023) ‘Far-right “Tradwives” See Feminism as Evil.’ Their Lifestyles Push Back Against ‘the Lie of Equality.’ The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/far-right-tradwives-see-feminism-as-evil-their-lifestyles-push-back-against-the-lie-of-equality-219000 [19 October 2025].

Cohen, Alina (2025) ‘Norman Rockwell Paintings That Once Hung in the White House Bound for Auction.’ Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/market/norman-rockwell-president-white-house-paintings-auction-2704973 [4 November 2025].

Joppke, Christian (2024) ‘Neoliberal Nationalism and Immigration Policy.’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369183X.2024.2315349 [8 November 2025].

Leidig, Eviane (2021) “We Are Worth Fighting for”: Women in Far-Right Extremism. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – ICCT. https://icct.nl/publication/we-are-worth-fighting-women-far-right-extremism [19 October 2025].

Shams, Shahrzad, Deepak Bhargava, and Harry W. Hanbury (2024) ‘The Cultural Contradictions of Neoliberalism: The Longing for an Alternative Order and the Future of Multiracial Democracy in an Age of Authoritarianism.’ The Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org [8 November 2025].

Stiglitz, Joseph (2024) ‘How Neoliberalism Failed, and What a Better Society Could Look Like.’ Working Paper. Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org [8 November 2025].

Williams, Katherine (2024) Women's Engagement with the Far Right: A Quest for a More Holistic Understanding. Compass Hub. https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/rec3.12495 [19 October 2025].

Zamora, Daniel and Niklas Olsen (2019) How Decades of Neoliberalism Led to the Era of Right-Wing Populism. Jacobin.com. https://jacobin.com/2019/09/in-the-ruins-of-neoliberalism-wendy-brown [8 November 2025].

POPULAR TOPICS

#subculture

Gurlesque: Poetics of the Bizarre, Ugly, and Feminine

#films

Mrs. Robinson, Countercultures, and Politics

#history

The Dutch Golden Age, Golden for Whom?

I also write articles here: https://feministpassion.blogspot.com/